DRF Luftrettung has built an advanced hoist simulator to develop the quality crews rely on the most: trust.

“I can measure precisely the trust a hoist passenger has in the crew,” said Sebastian Schneider, holding his thumb and forefinger apart to show the steel hoist cable’s diameter: 4.6 millimeters, or 0.18 inches. “When they’re attached to the hook, they are completely dependent on the hoist crew.”

In that single measurement lies the essence of helicopter rescue operations — a person’s life suspended not just by a steel thread, but by the accumulated training, judgment, and coordination of an entire crew working in perfect harmony.

It is upon this foundation of absolute trust that DRF Luftrettung has built what may be the world’s most sophisticated hoist training system. Inside a converted trailer that can travel anywhere in Europe, the German air rescue organization has created a simulator that merges cutting-edge augmented reality with traditional pilot training, addressing one of emergency aviation’s most persistent challenges: how to safely practice scenarios that are too dangerous to rehearse in real life.

From combat medic to innovation champion

The journey to hoistAR began not in a corporate boardroom, but in the military hospitals of a joint U.S.-German military collaboration, where Schneider spent time during his service with the German military.

The experience taught him that life-or-death situations require not just technical precision, but also unshakeable human judgment. After completing certified paramedic training at Medic One in the U.S., he transitioned from combat medicine to civilian emergency care when he joined DRF Luftrettung in 2011.

“I changed the focus from the medical to the teaching part,” Schneider said of his evolution within the company.

Since 2018, he has served as DRF’s chief hoist instructor, responsible for training all pilots, hoist operators, physicians, and paramedics across the organization’s operations.

“It’s a very happy situation when you can see the learning process … and by the end, you have created a new successful hoist operator, hoist pilot, or doctor. That makes me happy every day.”

But Schneider’s satisfaction in watching his students’ progress was tempered by a fundamental training limitation that has plagued helicopter rescue operations since their inception. DRF Luftrettung operates what Schneider describes as a “triple use” model unique to Germany, where the same crew and aircraft handle emergency medical services, intensive care transport, and hoist rescue operations.

This versatility demands extraordinarily comprehensive training, yet the most critical scenarios — cable failures, engine emergencies during hoist operations, oscillating loads — are precisely those that cannot be safely practiced in real aircraft.

The boundaries of training in live environments are personal as well as technical, and Schneider was frank about how they are prioritized.

“In real flight, you have limits. Firstly, I don’t want to die,” he said. “Secondly, I have the limitations from the manufacturer of the aircraft.”

He estimated that conventional training could cover 95 percent of required scenarios, but that final five percent represented the difference between competent operators and those prepared for genuine emergencies.

“I’ll give an example,” he said. “Cable cutting — you don’t perform this in normal flight.”

Genesis

The solution emerged, as many of the best ideas do, from an informal conversation over drinks. Four years ago, Schneider and his colleague Jörg Redetzky were discussing the training gaps when they conceived what Schneider laughingly described as a “strange, but in the end, very good idea.” Their vision: a mobile hoist simulator that could provide realistic training for emergency scenarios while integrating with full-flight simulators to train complete crews together.

“We were lucky that we had the trust of our CEO, Krystian Pracz,” Schneider said. “The system wouldn’t cost one or two euros — it would mean huge costs. They said, ‘When you say we need this and that it’s a good investment, we’ll make this investment.’ They trusted us fully.”

That corporate backing proved essential as the development process encountered what Schneider diplomatically termed “a lot of highs and lows.”

The technical challenges were formidable. The system needed to integrate seamlessly with Lufthansa Aviation Training’s EASA Level D Full-Flight Simulators in Frankfurt, requiring sophisticated networking capabilities and minimal latency.

the constraints of German TÜV trailer regulations: a maximum weight of 3.5 tonnes and a maximum height of four meters (13 feet). These limitations would make hoistAR truly mobile, but dramatically complicated the engineering challenge. Nevertheless, Schneider and Redetzky delivered.

“The magic is when you have a connection to the [pilot’s] flight simulator,” Schneider explained. “When the pilot flies with a bank angle or changes the attitude of the aircraft, the hoist operator feels the same.”

Achieving this synchronization required each system to maintain its own image generation database while sharing only position data — a solution that proved both elegant in its simplicity and robust in practice.

Virtual advantage

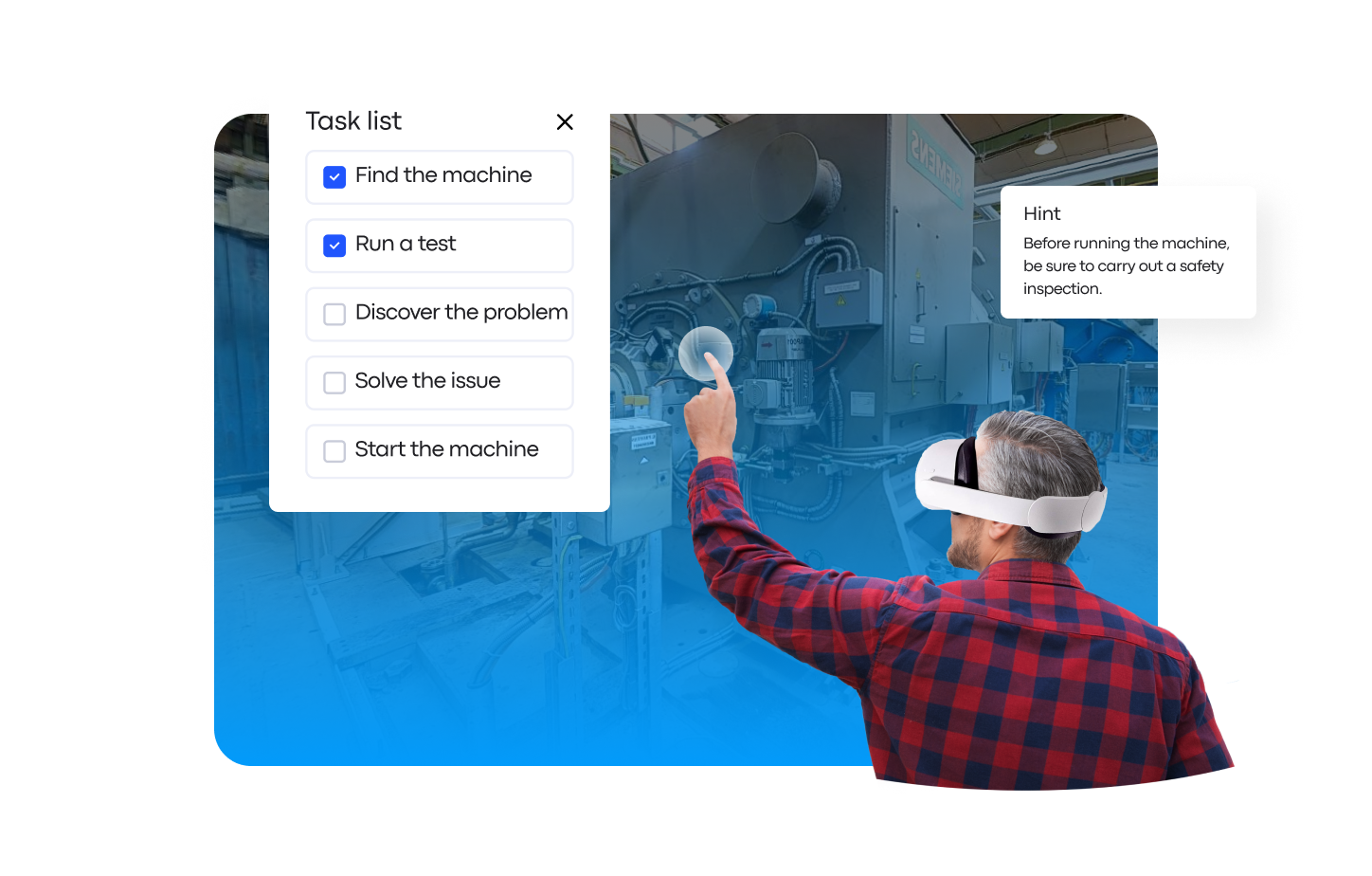

DRF Luftrettung’s choice of augmented reality (AR) over pure virtual reality (VR) reflects a nuanced understanding of training psychology — a debate that echoes across the aviation industry. While VR systems offer complete environmental control, AR preserves crucial tactile elements that Schneider believes are essential for realistic training.

“The hoist operator standing on the skid can see his feet and hands in real life,” Schneider said. “He can read a checklist on real paper, not as an analog.”

The system combines a physical hoist control pendant with real switches and controls, alongside virtual elements like the cabin environment and external scenery. This hybrid approach addresses what is often referred to as “negative transfer” — the risk that simulator training could actually impair performance if it fails to replicate the full sensory experience of aircraft operations.

The hoistAR system uses a synthetic cable rather than steel, but preserves the tactile feedback of hoist cable management that experienced operators rely on instinctively. Virtual scenarios can include not just routine operations, but also emergency procedures such as oscillations on the line, equipment failures, and challenging environmental conditions that would be impossible to recreate safely in real aircraft.

Yet Schneider is careful to position technology as a tool rather than a replacement for human judgment. His approach to training with night vision goggles reveals this philosophy.

“I say to the students that it’s only a tool in my toolbox. When I need this tool, I can use it. And when I don’t need it, I use another tool.”

Night hoist operations require what he calls “a little bit of a mixed” approach, using goggles as backup while maintaining visual contact with search lighting whenever possible.

Global reach from a German trailer

The system’s mobility proved itself in spectacular fashion during a demonstration that has already become legendary within the close-knit rescue helicopter community. Last year, Schneider and Redetzky drove the hoistAR simulator from Germany to Thessaloniki, Greece, for the International Commission of Alpine Rescue conference — what Schneider called “one of the strangest road trips I have ever taken in my life.”

In front of 600 delegates, they connected their simulator to a DRF Luftrettung pilot operating a Level D simulator in Frankfurt, more than 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) away, demonstrating integrated crew training across continental distances.

“We showed the training on the huge main stage from a podium,” Schneider explained. “It showed the system working without any latency.”

This capability opens possibilities that extend far beyond DRF Luftrettung’s own training needs. The system operates in two modes: one for basic hoist operator training, and another networked mode for integrated crew exercises. International customers could receive training by traveling to Frankfurt for simulator time while DRF brings the hoist trainer to them, creating a flexible global training network.

And its applications extend beyond traditional rescue operations, as hoist skills developed for medical rescue translate directly to offshore and industrial settings.

“You can use this system for training, maybe for a sea pilot transfer service,” Schneider explained. “Or for a transfer service in the operation of wind turbine maintenance in the future.”

The efficiency paradox

While DRF Luftrettung’s investment in synthetic training reflects broader industry trends toward simulation, Schneider is quick to address misconceptions about the technology’s primary purpose. Though cost reduction often dominates budget discussions, he argues that efficiency gains and risk reduction represent more significant benefits.

“In a simulator flight hour, I am so much more effective,” Schneider explained. “I don’t have to fly the transfer flight from the base to the hoist site. I don’t have to fly the return flight to the base. I don’t need the time for refueling.”

He estimates 25 to 30 percent greater efficiency in simulator training compared to aircraft operations, but emphasizes that the real value lies in keeping aircraft available for actual rescue missions.

Ecological considerations add another dimension to the training equation. “You can train in a risk-free, emission-free environment,” Schneider said, “I think that’s an important part of creating the future of training.”

As the aviation industry grapples with sustainability pressures, synthetic training offers a pathway to maintain proficiency while reducing environmental impact.

Yet the technology creates its own complexities. As helicopter training embraces simulation capabilities that were unimaginable a decade ago, the challenge becomes determining the optimal balance between synthetic and real-world experience.

“For the last 10 years, what [hoist training] has the helicopter business performed on the simulator? I think nothing,” Schneider said. “When I look at the next 10 years, I’m sure we will do more and more in the simulator and leave the real environment.”

That vision will depend not just on the availability of the technology, but also on the willingness of the industry — and the regulators — to adopt it.

“At the moment — and I must say at the moment — we have state-of-the-art technology for sure. But this technology doesn’t stand still, and I think the fear from some operators is that they don’t know the full spectrum of what’s available on the technology side,” Schneider explained. “We would like the highest level, or the highest number of credit points back from the authority to reduce the [required] flight time. But that’s not my focus, to only reduce the cost. I think that’s only a secondary benefit.”

The trust ecosystem

That evolution toward more synthetic training might seem to contradict Schneider’s emphasis on trust as the foundation of hoist operations, but he sees technology as enabling rather than replacing human connections. The simulator allows crews to experience failure modes and emergency procedures together, building the shared experience that creates confidence under pressure.

“The pilot needs to trust the hoist operator to give them the correct commands,” Schneider explained. “And the hoist passenger needs to trust the hoist operator to handle the hoist professionally and safely.”

The crew in the aircraft must also trust the hoist passenger, Schneider pointed out, as an entanglement of the cable or hoist connection could be disastrous for everyone onboard.

In the moments between the hoist passenger stepping out of the aircraft to the time their feet are firmly planted on whatever surface they are being delivered onto, they are all dependent on one another.

“I don’t have the view that the focus is always on the hoist operator and the hoist pilot,” Schneider said. “An important part is the hoist passengers — and in air rescue, our patients.”

The hoistAR system represents DRF Luftrettung’s belief that the most advanced technology ultimately serves to strengthen, not replace, human capabilities. In an industry where split-second decisions can mean the difference between life and death, the simulator creates space for crews to develop not just technical skills, but the deeper judgment that emergency operations demand — and deepen their trust in one another.

As DRF Luftrettung prepares to deploy the system operationally, Schneider looks toward a future where synthetic and real-world training blend seamlessly.

“In the next years, we have the ambition to perform a mixture of real and simulation flights,” he said. But regardless of how sophisticated the technology becomes, the fundamental truth remains unchanged: somewhere above the ground, a person’s life hangs by 4.6 mm of steel cable and the accumulated trust of everyone involved in bringing them safely home.

Quelle: